I stumbled upon an interesting quote today, one I think has a lot of merit for martial artists and self defense enthusiasts. Actually it’s two quotes but I’ll start with one:

When we look at any kind of cognitively complex field — for example, playing chess, writing fiction or being a neurosurgeon — we find that you are unlikely to master it unless you have practiced for 10,000 hours.

I truly believe this 10.000 hour rule applies in spades if you want to become a martial arts expert.

One of the reasons Loren and I got along well when we got to know each other was because we both like to do loads of solo training. Many practitioners only do their reps when they go to class. Then they go home and don’t practice until next class. I never understood that. As a teenager, I’d come home after class and repeat the things I’d just learned. The next day, I trained those again. Partly out of fear of forgetting them (I’m a slow learner) but mainly to just get better. Some of my classmates didn’t understand this was the primary reason why I progressed faster than them: I trained more.

I often tell my beginning students to do this too: practice every day. If only for 5 minutes, but do practice. When they take my advice, it shows: sometimes in as little as a week, they make huge progress. Five minutes a day doesn’t seem like much but it adds up. For some reason, us Western folks often think we’re wasting our time if we don’t train for at least an hour. That’s just not true. Repetition is the key. You need to get your reps in, regardless of how you do so.

Loren always emphasized this in his writing and videos, get your reps in. I think he’s spot on. I still try to sneak in as many reps as I can. My girlfriend is used to me practicing at all possible moments, regardless of where we are (though I have become more discreet over the years and don’t embarrass her in public too often anymore…)

Side-note: if you want to throw out the “perfect practice makes perfect” cliché, don’t. I’ll just tell you to go stand in a corner and count to 10.000…

I want to become a martial arts expert!

Cool, start training more! It’s that simple; But at the same time, it’s a lot more complex. Here’s the second quote:

Those 10,000 hours have to be invested in the right things, and as the disjointed nature of Hamming’s talk underscores, the question of what are the right things is slippery and near impossible to nail down with confidence.

This is where the plot thickens…

10.000 hours of training is a lot. You can boil it down to about three hours a day, seven days a week, for ten years straight. That’s a lot of training. Let’s assume you’re up for it but then you run into a problem right away:

How precisely do you fill those ten years of training?

- What exactly should you train?

- In what order?

- Which parts should you emphasize at which stage?

- When do you know you’ve been training the wrong things?

- Which training methodology should you use?

- Etc.

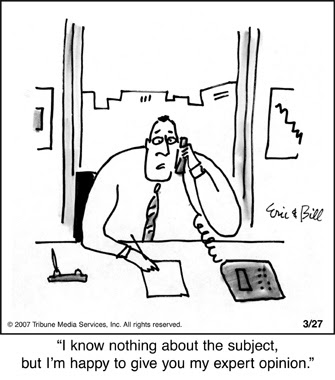

There are tons more questions in this list, too many to sum up here, but they bring forward the main problem the second quote illustrates: you have no way of knowing you’re going about it the right way. There’s just no way you can say 100% sure which are the right things to do in your training. IMO and IME, anybody who claims otherwise is trying to sell you something.

Sure, there are general blueprints you can follow and there’s a huge body of work available to draw ideas from. You also have easy access to tons of experienced teachers, people who’ve been there and done that. So if there ever was a time when you could find information on how to train martial arts or self defense systems, today is it.

But these experts aren’t you. They can’t be you. So they can never make the best decision for you specifically. Nobody knows better what you need than you. Of course, this implies you’re honest to yourself and aren’t delusional. But I believe the reasoning is valid enough: don’t count on those experts to do your thinking for you.

I still want to be a martial arts expert!

Good for you! My only advice would be to ask yourself: do you want it bad enough? Because 10.000 hours is a lot of time and effort. Without guarantees that you make the right choices as far as what you should be training. So it might take a whole lot longer still before you reach the point where you can consider yourself an expert. So I repeat: how much do you want it?

Me? I’m well past those 10.000 hours, so I think I’m entitled to speak. Do I consider myself an expert? Nope. I’m just a guy who’s been training longer than many people. I learned some things along the way (I better have…), made tons of mistake, have some skills but I still have a long way to go when I look at my teachers and others in the same field. Some of my friends have twice the amount of training that I’ve done and I’m nowhere near their level. Others have only a fraction of my amount of training but tons more live experience. In certain things, this makes them more skilled than me.

Frankly, I think labels like “expert” or “master” are highly overrated these days. There are very few people I personally think deserve those titles. Invariably, all of them refuse to use them. They prefer you call them by their first name. Those are the people I look up to. Them and my teachers are the people who’s opinion I care about. If they say I’m going down the wrong path, I listen up. If some anonymous Internet troll talks smack about me, I couldn’t care less. Life’s too short for wasting my time on that crap.

The best advice I can give is what my teacher wrote in one of his books:

The word “student” comes form the Latin verb “studere” which means “to be eager” or “diligent”. If you want to be an expert, you’ll have to become a lifelong student. He gives a couple of guidelines for this, writing that a good student:

- Practices.

- Looks and listens.

- Thinks, then asks.

- Is neither too harsh nor too soft with his training partners.

- Constantly seeks to learn, both inside and outside the class.

- Trains and competes honestly.

These guidelines are not hard to understand. But I’ve found them sometimes very hard to follow. It’s easy to be too hard on a training partner or to be dishonest with yourself when you train. These things don’t necessarily happen out of malice, they’re just part of being human. When they happen to you, correct your mistakes and move on.

All I can add is that when you try to follow these guidelines, chances are good you’ll not waste too many of those 10.000 hours on the wrong things.

That’s it? That’s all you’ve got?

Nope, just one more word of advice: Above all, have fun training. If it isn’t fun, you won’t ever make it to those 10.000 hours.

.

Josh A. Kruschke says

Good post.

If you haven’t already red it you might like the book “Outliers.” Can’t seem to find it so can’t give you the authers name.

Josh A. Kruschke says

Also, the leangth of time, it seems to me, revolves around the complexity of what you are studing.

Wim says

Outliers is on my list of books to read. The 10.000 rule is often credited to Gladwell but IIRC, it was discovered a lot earlier.

Kevin Keough says

Wim,

I just had a complete blast reading this essay. Nothing else to say but “Thank you”.

Kevn

Wim says

Thanks for the kind words Kevin. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. Have a great end of the year!

Rick Matz says

1 – Natural talent

2 – A good teacher

3 – Perseverance (the 10,000 hours)

You still need the other two elements.

Adam says

I found this one thought provoking Wim. I agree to be a true expert, a LOT of time needs to be spent on training. You touched on it before when you ask WHAT needs to be practised. I subscribe to the Pareto Principle of 80/20, even 90/10. That 20% of what we do provides 80% of the results. I think much of what may find its way into such a training regime would be wasteful.

The secret is to find the most effective part out of a regime which would normally be around 20% and then cut out the rest. But then, do that key 20% component 100% of the time. That shortens the number of hours to 2,000. It may even lessen it more in that there is less of a time gap between practising those key components so perhaps learning is accelerated even more?

What is the key 20%? Those skills needed right now. For a beginner, it is pure self defence skills. These are most important. What if that student knew they were going to be attacked within three months from an attacker who would try to use the element of surprise? Train for the most likely scenario for their lifestyle. Unfortunately for instructors, it is inconvenient to be able to provide tailored self defence training for each student so unfortunately all students do one size fits all training…

Once a good base of self defence skills are learnt (which includes a knowledge of violent crime, victim selection, physiological responses, Coopers colour codes etc…), time can then be spent on sharpening the tools and working on the basics and then so on and so on…

I agree Wim that it can be hard to identify what to practise first in such an 80/20 approach but I also believe people can train smarter. It just takes more work to tailer such an approach for each individual circumstance. On top of that, these change as well. Just getting started is the hardest part.

Thanks for the post.

Wim says

Adam,

IMO, the 80/20 principle doesn’t come into play here. 20% still leaves plenty of work to be done when we’re talking about self defense training. I don’t think there’s a short cut there, the material is plenty complex enough.

Mind you, I wrote about getting to a level of skill that is at the highest possible level, comparable to the level Olympic gold medalists reach in their sport. For that, I think even 10.000h isn’t enough. But it’s also a level very few people would ever need to be at. For the average self-defense scenario, you don’t need to be at this level IMO. You can get there a whole lot faster than at the “genius” level mentioned in the speech.

Don says

A little bit every day, as you stated,even 5 minutes, is a great way. Only have two minutes free time waiting for the family? Go do a form. Go hit a speed bag for one round.

Want to increase the stance holding time (for CMA folks)? Hold 30 seconds at various times throughout the day, in addition to your regular workouts.

Fitting in stretches at your desk during the day will help in your overall flexibility goals (and help relieve stress and boredom).

Thanks for the good reminders.

Jon Law says

The word “student” comes form the Latin verb “studere” which means “to be eager” or “diligent”. If you want to be an expert, you’ll have to become a lifelong student

It’s also very easy to become dishonest with yourself when you train

I like these two quotes very much along with the fun part. It all goes hand in hand imo. If you really want to progress you really have to remain keen, curious and diligent and to be honest about your training, this is good advice.

Someone once said to me that when you start training you don’t realise that 90% of training is on your own. I find this to be so more so over time and as such your advice holds.

It;s pointless putting in 10000 hours if you are not honest with yourself.

And Gladwell should not be credited it with the 10000 hours, he merely took the premise on for his book., which is great by the way.

Wim says

Glad you like the article Jon. And I couldn’t agree more about the 90% of training on your own. That’s been my experience exactly.

I know Gladwell just ran with it, check out the previous comments.