This morning, I was listening to Kris Wilder and Lawrence Kane’s podcast #24 and they make a tremendous point in there. It’s in the section called “Mr. Shiko Dachi and Mrs. Naihanchin” so you might want to listen to that part first before reading on. They explain some of the differences between both stances and the reasons behind them. Not in great detail but enough to give you an idea of how different both stances are despite looking so similar.

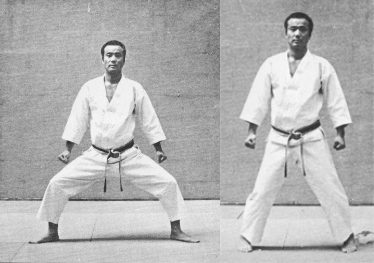

If you aren’t into Karate (I’m not either so I just searched the web for these pictures), here are the two stances:

I didn’t find one of naihanchi in a lower position but other than that, as you can see, they’re pretty similar:

- Upright back.

- Weight in the middle.

- Legs bent.

- Body facing forward.

We can argue over the details of this list but the similarities are clear, especially when compared to other karate stances.

The point Kris and Lawrence make is that too many karate practitioners look at these similarities and conclude that both stances are therefor the same. Nothing could be further from the truth, as they go on to explain in the podcast, and it leads to all sorts of trouble in the practitioner’s training and skill level. Again, listen ot the podcast for more information about what goes wrong.

I’m not going to comment on these two karate stances as I’m not qualified but I am going to take this a bit further and make a bold statement:

The #1 reason why you’re not making any progress in your martial arts or self defense training is that you are making the exact same mistake.

I know, bold. But I think it’s a valid claim and we pretty much all make that mistake in our training. Me, you, and everybody else too. Before I go on about the reasons why this happens, some examples:

- A while ago, I saw a video of somebody performing a weapons form I practice. The practitioner obviously had a lot of training; he was fluid and put a lot of details in his form. However, he also showed some fundamental errors. The most glaring one was when he did an upward block, followed by a counter-cut: he systematically blocked too low. His sabre never came high enough to actually protect him from the vertical strike he’s supposed to be defending against. When you watch that practitioner’s video and then one of somebody doing it correctly, you’ll probably miss the error, unless you know it’s there. The sword is only a few inches higher but in application, it’s the difference between life and death.

- Look at the vast majority of knock outs in boxing that are done from the counter. When you throw a right cross, your right flank is exposed. There’s nothing you can do about that because you have to use your right arm to punch and therefor open up that flank by default. However, how many times do you see a KO scored exactly on that target against a cross? Not that often. What you see a lot is fighters getting countered because of the opening they leave to their head by dropping their right shoulder from their chin or not bringing their arm back to the on guard position quickly enough. Those are technical errors. A cross like that looks very similar to one that is performed correctly. But in the ring, it’s through those errors that you get scored upon. Small difference in technique, huge difference in results.

- The same goes for the jab. Throw a perfect jab and you’re covered on all sides of your face; throw a jab while keeping your right hand an inch or two lower and you’re wide open to get knocked out. This is a classic mistake (and a very human one we all tend to fall for) but it opens you up for devastating counters. Just look at a few boxing matches and you’ll see it. Watch this video at 5min50 to see the legendary Rob Kaman explain this concept to a fighter. Again, small difference in technique, gigantic difference in the results you get in a fight.

- The difference between rear hand in the muay Thai and boxing jab is small but crucial. In some boxing styles, they bring the rear hand in front of the face when using the long range jab. One of the reasons is to make faster combinations but also catch the opponents counter punch. It’s not my preferred method of jabbing but it works in boxing. However, in muay Thai, you almost never see that technique. Simply because it exposes your face to kicking techniques while you’re leaning forward to strike from afar. This isn’t an issue in boxing as kicking isn’t allowed but it is in muay Thai. If you haven’t experienced this before, it sounds an unlikely scenario: a guy kicking at head level at the distance where you throw a jab? Yup, and then some. Peter Aerts specialized in it. A couple minutes into this highlight, you’ll see him land that high kick at exactly this distance and sometimes even closer. Take a look at where his opponent’s hands are every time he lands the kick: they’re always in the wrong place to defend against it.

Here’s another example but instead of a jab, it’s a lead hook. See how the rear hand drops and leaves him wide open for the kick? Had the hand been in front of his face like in the jab I mentioned, the result would have been the same. The most important place to keep your rear hand in a muay Thai punch is high against your face.

- A friend of mine teaches a very specific style of Indonesian martial arts. It’s been in his family for a long time and the other styles he practices also come from a pure lineage. He’s extremely skilled and has lots of real world experience to back it up. In a nutshell, he’s “Good!” (He deserves that the capital “G”, and then some…) His style is also structured in a very specific way, one you don’t really understand until you’ve practiced it for a long time. On the outside, it looks similar to other Indonesian styles and and apparently, players from other schools sometimes respond to his teaching with “Oh, we do that too.” or “I know that already”. Unfortunately, they don’t. They spot the similarities with what they learned from their own style and figure that’s all there is to it. But they don’t see beyond these and therefor miss the crucial differences that make the system so effective. I’m going to stay vague about the details on purpose as not to make my friend feel uncomfortable but please take my word on it that these differences are where it’s at.

These are just a handful of examples of seeing the similarities and not the differences. There are many, many more and you’ll find them in all aspects of the martial arts or self defense systems, not just in techniques. I picked a couple easy to understand examples to better make my point but things aren’t always as clear. Sometimes, the differences between seemingly identical techniques and concepts are extremely subtle. The consequences aren’t, however. Those end up right there, in your face…

Why does this happen?

I believe it’s human nature to fall into this erroneous way of thinking. Sometimes it happens by accident or it’s a subconscious issue, other times, people knowingly refuse to see the information that is right in front of them. There are probably a bunch more reasons but here are some I think cause this myopic thinking:

- Not knowing any better. Sometimes, it’s a simple as not thinking things through. You simply don’t even consider that there could be a difference. You learn something, it makes sense to you and then you accept it as “true” which invariably makes all other possibilities false. And then you don’t question this truth anymore, so it simply becomes a fact for you. Kind of like gravity; you don’t question that either because it’s also true.

- Oops! We all make mistakes, it happens. Sometimes you think you’re doing it right but you aren’t. There are subtle differences between what you think you’re doing and what you actually are doing. There’s no malice involved, just an honest mistake.

- Ego. It can be very hard to discover you’re wrong about something. Especially if you’ve invested a lot of time and energy in it. It gets even worse if you’re a teacher and all of a sudden, you have to admit to yourself and your students that you are wrong. A lot of people can’t handle this; they prefer to rationalize until they believe the differences are actually insignificant and there’s no reason to make any changes.

- Bad teachers. Some teachers just don’t care they’re selling crap to their students. They’re in it for the money or self-gratification and don’t mind if their techniques don’t work. So to them, all this isn’t an issue. They just don’t care.

- Bad lineage. I’m not hung up on lineage but it does have some merit when you are in a school that has a legitimate one. If the lineage is sound, there’s a good chance the curriculum has kept all the components that were in the style when it was created. If the lineage sucks, then the odds are good some parts got lost over the years. When that happens, the information you need to know about those small differences is simply no longer in the system.

- Necromancy and patchwork. A friend of mine views most of the Western sword fighting schools are practicing a form of necromancy. He believes those practitioners are trying to resurrect lost arts (we don’t really have a living tradition that passed on how knights from medieval times fought…) by interpreting old texts about fencing and sword fighting. By default, you can never know if you are right when you do historical research on dead traditions. It’s always going to be theoretical for the most part. So what do a lot of people do? They create a system from those texts and then patch the parts that don’t work or those they don’t understand with information from other styles. Often, that information comes form Asia. At best, you get a functional blend that has some value. At worst, you get a jumbled mess. But like I mentioned above, ego often takes over and makes it hard to admit all this to yourself or your students. I can’t say I entirely disagree with my friend…

There are probably more reasons still but I’m going to leave it at that. Time to wrap it up.

So what?

So everything. For the reasons I explained above, I think we all make this mistake to a certain degree. We watch somebody perform a technique or they explain a concept from their system and we think “Yeah,we have the same thing in our style.” which is another way of saying “I know that already and don’t have to pay attention.” So you just move on and don’t think about it any further. As a result, you don’t get the information you need at that point in time or you end up ingraining things that don’t work as effectively as they could. If you have enough of those issues going on, you’ll slow down and eventually stop making progress in your training.

I know this isn’t a fun topic to think about but that doesn’t mean you should sweep it under the rug. OK, I’ll go first:

I’ve been wrong so many times in my training, it’s not even funny anymore. What’s worse, I’m an opinionated and argumentative bastard too. So I’ve had my fair share of eating not just slices of humble pie but the whole damn thing. It was never fun for my ego but if I’m really honest about it: The times I’ve been wrong the most, whenever I was called upon assuming things were similar to what I already knew and they weren’t, those were the times I made the most progress. If at first I didn’t know the problem existed, I was very motivated to correct it when I was confronted with it. Each of those instances lead me to a leap forward in my training. They were often crucial in overcoming the lack of progress I’d been feeling for a while. Not always, but often enough to see the pattern.

Again, it always stings a bit having to admit you’re wrong. But it’s definitely worth it. You’ll make progress once again and isn’t that why you’re training in the first place?

UPDATE:

I eventually “invented” a law based on this concept. You can read all about Randy’s Law here.

Rick Matz says

In other words, you’re better off if you understand what you’re doing; every bit of it, and not just going through the motions.

That’s good advice for living, actually.

Wim says

Yup, but it’s easier said than done. :-)

Rick Matz says

Amen, brother.

Richard Martin says

This would be exactly why I gravitate to the internal martial arts. Typically they are practiced with exactly this in mind. In my humble opinion, this is one of the reasons that we move so slowly in practice, not so that we can daydream, but instead so that we can focus on all of those details.

Wim, your post is “spot on”. Thanks for a great blog.

Wim says

Thanks Richard, I appreciate the support.

Beto says

Very good post Wim, indeed is hard to be self critic and most of all accept when one is wrong, But at the end of the day,like you said, is the only path for improvement. Thanks!

Dennis Dilday says

I read this excellent post and thought about it realizing that it was the work of the teacher within the context of this post that struck me. Assuming you have something of value to teach and it’s subtle and complicated and takes time to learn, there is a dilemma appreciated best by those who understand neurological habituation (learning).

This dilemma eventually teaches you to strike a fluid balance unique to each situation and each student. That is: do you harp on the technical correctness of infinitely minute detail as you introduce this detail to the student you want to teach; or do you give the generalities and whittle away at the discrepancies once they get a vague jist of what is being taught. Meanwhile how much to you tell them of what it is they are really learning.

It’s so easy to overload a beginner with minutia both in terms of correctness of there body in motion and mentally in terms of what they can retain about what the significance is to what they are learning.

A recent issue of Fitness Journal features Tai Chi and includes a fair article on the subject of teaching. In it their favorite guy (who coincidently is also a mental health worker:-) talks about how important is it to create a situation where the student somehow experiences (internally is what I think he was meaning) whatever it is you are trying to teach. I found that an important reminder: its serves as a useful guide in the process of teacher, for me anyway.

In my experience it was way too easy to chase students off by insisting that they get every detail as close to right as their bodies would allow right from the start so that they would not be practicing (and therefore memorizing neurologically) improper alignment, movement, technique, whatever. Combined with way too much talking, this serves to overwhelm and reinforce any thoughts in their head that they just can’t do this stuff. Bad move. Worse yet when you insist that the student repeat the small stuff so many times that they get bored thinking it isn’t fun yet and is this all there is too it. (Here you might note that this approach may be considered traditional: they used to get away with it, not so much any more.)

It took a while to notice and appreciate the balance I referred to earlier in the teaching of my own teacher who seems to have an instinct for applying just the right amount of correction at any given time. He seems to know too, when it isn’t a good use of his time to attempt to get more out of a student than the student is going to give, and let it go at that.

I think my points will be appreciated by the teachers and will serve to re-enforce Wim main points about knowing subtle distinctions and being aware of subtle discrepancies to the extent one can. Good teachers seem to know they are also the student; good students learn and then assimilate their learning in the face of multiple contexts and situations, refining and discovering more along the way. (All of the many many Ah Hah! moments experienced within the Form practice are just simple and common examples.)

This is too long… I hope it helps.

DrD

Wim says

Dennis,

Nowadays, I teach a very basic, no bells and whistles way with beginning students. When I see them getting certain points, then they get more details to work on. That process never stops and it is driven by the student’s desire to learn. If they have it (like Dan wrote, student comes from “studere”, meaning “to be eager”) then I can bring them further down the path. If all they do is show up for practice to have a break from their daily lives, then I’m limited by their lack of effort. Because our art takes a lot of effort to make progress in,so they need that desire to begin with. It’s no problem for me if they don’t, we all train for our own reasons but it just puts a limit on how far they can take the art.

That said, it’s indeed a skill in and of itself to give a student the right type and amount of stimuli at every stage in his learning. The way I learned it was to ask myself the question “which correction does he need the most right now?” before telling him something is wrong. If there are more than one, I usually give a general one (back is not straight, double weight, etc.) along with a specific one (keep your striking hand on center line in “Brush knee” instead of in front of your shoulder.) No more than that. It seems to work for my students.