A while ago I posted a video on my Facebook page and gave a short explanation of the dynamics involved. One of the things I mentioned is “Montie’s Law”, which is:

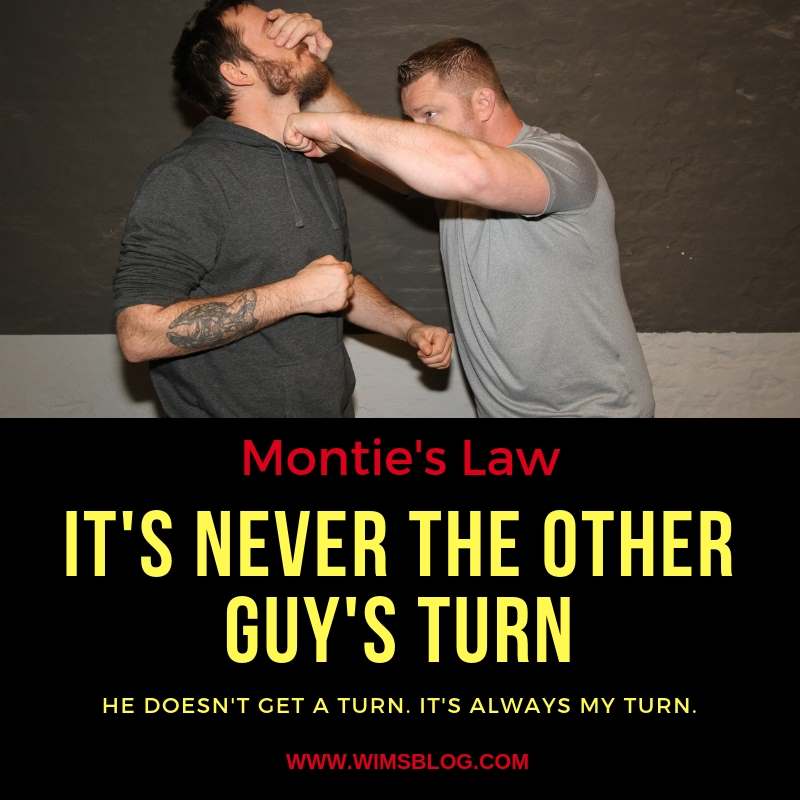

It’s never the other guy’s turn.

This needs some explaining, so here goes.

Montie is a LEO friend of mine, who I interviewed for my podcast a while ago. He’s done different kinds of work in law enforcement and is now involved in counter-terrorism. He is well-trained, experienced, smart and we have a matching sense of humor. As a result, we get along famously and getting together means copious amounts of alcohol are consumed… In short, I would trust him at my back any time.

Back on track: a long time ago, he explained his strategy for fighting and spoke the words I now call Montie’s law.

“It’s never the other guy’s turn. He doesn’t get a turn. It’s always my turn.”

He swarms his opponents with constant attacks and uses overwhelming force to get the job done. If the opponent is lucky, he might get in a first shot, but after that, it’s never his turn again. I liked that a lot and expanded that idea into what I use it for now.

Montie’s Law is one of the biggest disconnects between traditional martial arts or combat sports training and real-life attacks: the level of violence doesn’t necessarily get cranked up slowly and gradually. It can go from zero to 100% in a fraction of a second.

That doesn’t always happen, but the possibility for it is always there, which is the biggest issue you need to be aware of.

Look at the video again. As soon as that first punch lands, the victim is groggy and has a hard time standing up. He isn’t knocked out, but – and this is the critical point – he is no longer able to defend against the next attack. When that next attack comes, it doesn’t matter if it is less effective than that first blow because it still does enough damage to lower the capabilities of the victim. This progressively diminishes his ability to stop the aggressor and so each next blow lands as well. The result is a vicious circle the victim can’t get out of.

It’s never his turn…

The moment he starts to go down, he is incapable of doing anything other than taking more damage. A few seconds later, he is unconscious and the stomping begins. All this, from getting hit by that first punch.

When I explain this to people, I often get a response of “yeah, yeah, we know.” Then they proceed to train as if this isn’t an issue they need to handle. This in turn leads to unrealistic training or training that depends entirely on being able to avoid getting hit. Or worse, knowing they can get hit but pretending they can take that punishment without consequences. I call this the “Street Fighter mindset.”

Many years ago, there was a video game that became extremely popular, Street Fighter. They still make new versions of it today and there are hundreds of similar games. They have a basic set up:

- Two characters fight each other.

- They both have “health bars” and you decrease the energy in it each time you land an attack on the other character. When his bar becomes empty, you win.

- Regardless of how full or empty your health bar is, your punches and kicks always have the same speed and power. The same goes for your ability to block attacks and use footwork.

As a simulation of a real fight, it’s not a bad analogy: if you hit somebody long enough, they eventually go down. But it’s the last point that has the disconnect I mentioned above. In the game, getting hit doesn’t change how well you can fight; in real life it does. That is why Montie’s law is so effective: if your opponent never gets a turn, his “health bar” empties out with each successful attack you land. That leaves him less and less able to defend himself against the next one. This continues until he is down and out.

The key point is that just one successful attack can put you at a disadvantage you can never recover from.

Train with this concept in mind, always.

But what about!

Does that mean you can never get out of a bad spot when somebody surprises you and gets the first hit in? No, not at all. Training recovery techniques should be an integral part of your curriculum, similar to failure drills in firearms and other weapons training:

- What do you do when the gun malfunctions? You practice how to clear it.

- What do you when you stab with a knife and the opponent evades the attack? You practice following up with recovery techniques or secondary attacks.

At no point should your training involve a mindset of “Well, my awesome technique just missed, so I have to give up and die now.” On the contrary: you always train to survive, to escape, to overcome. However, you also have to acknowledge the realities of violence: if an aggressor gets the first shot in and it’s a good one, the odds of you making it out in one piece drop dramatically. They don’t necessarily go all the way down to zero, but they sure don’t look good. Try your utmost to get out of that pickle, but accept that things are looking mighty bleak for our hero…

That is the negative side to Montie’s Law: if your attacker gets the drop on you, you might never get a turn. In the video, you can see an example of how bad things can get. Just so you know, there is far worse than what happened to that man…

How do you train with Montie’s Law?

The positive side of Montie’s Law is this: if you train correctly, you can stack the deck in your favor so it is never the other guy’s turn. There are different ways you can do that:

- Preemptive attack. The most effective way to end a fight is not being there to begin with. The second most effective way is to attack first. Now most of you will already know this so let me add some nuances I think are important: attack first, making sure your technique lands with sufficient power to knock your opponent out or down, break his balance and structure, injure him, switch his mindset from offense to defense and buy you the time to land your next attack. Or any combination of the above, preferably all of them simultaneously. If you fail to do so, that first hit you land risks merely pissing him off. This forces you to face an opponent who is now hellbent on (at best) beating you up. Attacking first isn’t enough; you need to make it count too.

- Overwhelming, continuous attack. This concept is illustrated well in the video I mentioned in the beginning. Obviously, I don’t justify this attacker’s actions. I only use them as an example of how overwhelming, continuous attack is an effective strategy and how it can be used in real life. Here’s how he applied it:

After landing that first sucker punch, he throws a barrage of wild punches that overwhelm his victim. In the space of a few seconds, he throws about twenty non-stop punches. It doesn’t look like many of them land cleanly, but that is not important at that point. His victim keeps on receiving hard percussive impacts, each one shaking up his already scrambled brain a bit more. The punches also drive him to the ground, where he is both unable to escape or defend himself effectively and stomping is the logical and instinctive next step for the attacker.

- Tactical progression. Every martial art and combat sport uses this concept. Some do so only in a limited way, others dig extremely deep into this concept. I will stick to self-defense as this is the topic at hand but know that the subject is much broader than this.

In short: each technique sets up the next one. Like a good pool player sinks one ball and lines up the next one with the same shot, each move you make sets up your next technique. When used correctly, each subsequent move places your opponent in an even worse position, hurts him some more (or in a different way), takes away his weapons and pushes him closer to defeat (whatever “defeat” may be…).

This can be as simple as throwing a quick eye jab with the lead arm to line up a power punch with the rear arm. Or it can be as complex as the Kuntao I learned from my late teacher Bob Orlando. For an example of that, look at this video of him slapping me around. If you slow it down, you can see that each movement not only sets up the next one, but it also uses instinctive reactions his attacks trigger: the slap to the groin tends to make people’s heads come down. The following upward strike then comes in at a head-on collision and raises the head again. It also places Bob’s right arm in the perfect position to swing my arm through, which in turn whips my head forward into his incoming elbow strike. And so on, until I am down and out.

For the record, this is Bob going slow and stopping long enough at each point so the camera picks it all up. He was more than capable of going faster, hitting harder and chaining it all together into a fluid combination.

The most effective martial arts and combat systems I know combine all these elements, simply because they yield consistent results. Which brings me to another nuance I need to add.

In a comment to my original posting of this video, Marc wrote the following:

I think that the other guy never gets a turn problematic as it can lead to excessive force. If for instance, a smaller female was being pestered by a guy in a secluded location and was breaking the boundaries that were being set by the female then I would definitely give her the benefit of the doubt in such circumstances such as in she reported it and the guy was found unconscious or badly injured where she said she was feeling unsafe due to what I described and due to a probable size and weight difference.

However if two guys going at it near a bar and one is beaten to a pulp and no weapons are involved then the victor would in my mind be under suspicion of using excessive force.

The idea of using minimum force necessary to deal with a situation for self defence does not seem compatible with the other guy never gets a turn as for me self defence is to resolve a situation not dish out a revenge beating.

I’m going to paraphrase my response to him here:

The one does not exclude the other. Simply put: you hit until there is no longer a reason to hit him. You stop when it’s time to stop and train for that.

When is it time to stop?

When there is no longer a threat or when you can safely exit, which is often the same thing.

How many times you hit him before that happens is irrelevant in that regard; hit him until he is no longer a threat. If it’s only once, that would be awesome, but you already have all your ducks in a row should you need to follow-up. Montie’s law means you are always positioned in such a way that you can deal out that second, third, fourth, etc. technique if necessary. You don’t have to rearrange your weapons, reposition yourself, etc. to do so; all that was already taken care of with each previous attack.

So minimum force is the default, but you train to have plan B, C, D and so on ready to go. Montie’s Law means the other guy never gets another shot at you. That is your goal and your tactics should take this into account.

Conclusion

Implementing Montie’s law in your training takes some time and effort. It’s a continuous process instead of a one-time goal. Most of all, it’s a mindset: you train for it and expect attackers to use it against you as well.

This article was originally published in my Patreon Newsletter of July 2017. If you would like to receive it too, join me here at Orange Belt level or above.

Matthias Duelp says

this is what is taught in most, if not all traditional systems. For example it is the core of the German school of fencing, where you are to go from the “nach” (“after”, since being under attack) through “indes” (“at the same time”) into the “vor” (“in advance”). “indes” is the critical point to take the initiative from your opponent. You find the same in traditional karate’s “sen no sen” etc. – deplorably it was rarely understood in the martial sports context …

Wim says

Indeed. This is what I replied on Facebook to somebody who made a similar comment like yours:

” It’s not one particular art per se, but more practitioners and their interpretation of it. E.g.: those who only take ikken hissatsu literally and are under the illusion that if they train well enough, one blow will be all they need. I’ve seen my share of such practitioners, and then some (though in other arts too.) You seem to practice karate, you’ve probably seen them too then. If not, then you are a fortunate man indeed.”

I would add for instance the way many Filipino martial arts practitioners approach stick work to this list too. There is a huge difference between what the old school escrimadors do and what you see nowadays.

Mark says

Great article.most people dont realize this is the truth for self defense untill they are on the receiving end of it.