When I was a young boy, we had a bookcase filled with a wide variety of literature. Most of it was well beyond what could interest me at the time but there was one book that would always draw my attention: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I eventually ended up reading it and liked it a lot. As I grew up, I read the other books and one of the things I enjoyed about them was that Holmes was a gentleman but also a fighter. He could kick ass if he needed to because he practiced boxing, fencing, stickfighting and as it turned out, martial arts:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle mentioned in one of the books that Holmes practiced a martial arts style called “Baritsu”.

Years later I would find out the style had actually existed but Doyle either misspelled it on purpose or made a mistake as the correct name is “Bartitsu”.

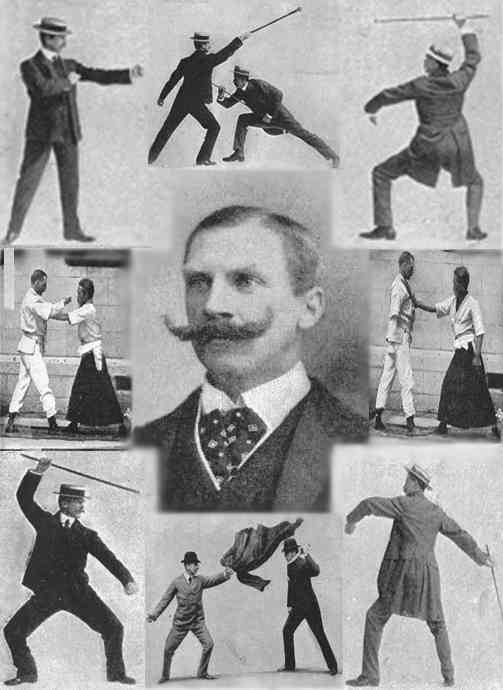

Bartitsu was created by a certain Edward William Barton-Wright who lived in Japan for several years and learned martial arts while he lived there. When he returned home, he created his own art, which was a mix of Western and Eastern practices. In many regards, he was a pioneer:

- He was one of the first (if not the first) to teach Japanese martial arts in the West.

- He cross-trained and could perhaps even be called the mixed martial artist of his day.

He had some commercial success with it at first but eventually ended up in financial trouble and the art died out. Barton-Wright died a broke and lonely man.

Bartitsu was re-discovered in the early 2000’s but only really shot back into the limelight when Robert Downey Jr. kicked some butt in the Sherlock Holmes and the Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows movies. Here’s a fight scene from that second movie:

Today, you can once again find a growing number of people practicing and teaching the art. You’ll also find books and videos on the subject by these experts. Here’s the thing:

Where did they learn the art?

Barton-Wright seems to have died without leaving many students who went on to teach the system. So unless somebody suddenly steps out of the shadows with such claims (and preferably some proof…), the lineage is broken and dead. So there are no actual people around who can claim to have learned the art through the generations in their family or anything like that. Again, if I’m wrong, I’ll gladly admit to it but so far, no luck.

If there are no teachers, then perhaps these new practitioners studied a library of manuals or perhaps some video footage of those times? Alas, again no luck. As it turns out, Barton-Wright did not leave a huge body of work behind. There is indeed some written material but it is both very limited and not all that impressive by today’s standards. If you’d like to know more, use Google a bit and you’ll quickly find those original pieces. Both the pictures and explanations are severely lacking to form a comprehensive curriculum.

So again I ask, where did these people learn the art?

I’ll answer it this way: they didn’t. They re-invented it.

From what I’ve seen (which admittedly isn’t everything), practitioners are just grabbing those old texts and then start studying and practicing to make the techniques come to life. In and of itself, that’s not a bad thing. However, there are limits to this method, which a friend of mine calls “necromancy”:

- You’ll never know. As there is no teacher alive who learned the art, no in-depth documentation of the curriculum, you can never be sure if your interpretation is right or wrong.

- Your knowledge limits your results. Martial arts styles and self-defense systems are nor created in isolation. They are formed because of a need in that specific day and age. In other words: when you start interpreting the techniques, you also need information on how crime happened back then in London as Barton-Wright apparently geared his system specifically to that city and as a system of self-defense (not a sport). So to make an even half-way decent attempt at re-creating the system, you need to do an extensive study of both the history of England in those days, the specific types of violence people faced, the way citizens viewed both violence and self-defense and much, much more. There are sources for this kind of information, but they aren’t necessarily available on the Internet. E.g.: how many current Bartitsu teachers have had access to (let alone made an extensive study of) the archives of Scotland Yard to form an educated opinion?

- Is it worth it? Before you embark upon such a quest, you need to ask yourself a question: how good was the system to begin with? Are there records of tons of practitioners using it successfully in self-defense? Or was it just a passing fad for the rich, as history seems to suggest? In other words, is this system even worth the time and effort it takes to recreate it, without ever knowing if you’re doing a good job or not? These are uncomfortable questions to ask but that doesn’t mean they should be ignored.

Here’s an example of somebody teaching pugilism from the curriculum. Now I’ll let you be the judge of the effectiveness of these techniques but personally, I think there are many issues with them. Not the least of which is that in the first two punches shown, he’ll break his knuckles every time he strikes using that specific angle with that specific wrist position unless he hits his target perfectly…

Another problem is the on-guard position. It is an antiquated one that, though it has benefits and made sense back then, is no longer used today. Not in competitive boxing gyms, and certainly not as a self-defense oriented boxing style. There are reasons for that but I’m not going to go into them here. What I’d like to point out is this:

Though there is very little documentation on Bartitsu, there is plenty of information available on the boxing from that era, as well as the evolution it went through from then until now. There are reasons for the change in on-guard position (and it’s not only about fighters wearing bigger gloves than back in those days) so it would make sense to implement these changes when using those techniques. But doing that invariably changes the curriculum. The way these things work, making one change can affect the entire system and before you know it, you’re re-engineering everything. Eventually, you’ll have something very different than what Barton-Wright taught. Which only goes to prove that no matter how strong a necromancer you are, you can never resurrect a zombie so well that it is the same person as in life. Unless you count Dominga Salvador of course, but I digress…

Along with all these problems, there is another one: the very human tendency to fill in the blanks or patch the holes with information from other sources. Given the problems I listed earlier, it’s common to run into problems while trying to make the system work. Instead of abandoning the whole issue, people often look at other arts for solutions. E.g.: at least one instructor who produced an instructional video on Bartitsu acknowledged that he is using his background in another Japanese martial art to interpret the curriculum. Which is not wrong per se but it is one more ingredient added to the mix that was not in the original recipe. Given as there’s nobody alive with 100% accurate knowledge to comment on this inclusion, there is no way of knowing if this is a good thing or not.

I’m not saying it’s impossible. I’m saying it’s difficult and there are no guarantees you will succeed.

Practitioners of Eastern martial arts styles have faced these problems for a long time. Some have found successful ways of handling them whereas others have done more harm than good. Still others are hypocritical bastards who don’t care about any of it. The only thing they see is an opportunity to make money by trying to develop “the next big thing” in the martial arts and self-defense market. These opportunists will always exist. However, in today’s world of 24/7 global communication, social networks and accessibility of records and sources, those pirates have an increasingly difficult time spreading their lies. It has just become too easy to check and verify their claims.

Given the only very recently renewed interest in Bartitsu, it’s bound to run into the same problems Eastern arts faced several decades ago. Here’s hoping they can learn from the mistakes that were made back then.

I understand this article may offend or annoy some people so in an effort to be clear, some more points:

- I didn’t say that all Bartitsu teacher are crooks.

- I didn’t say they all suck.

- I didn’t say they don’t know what the hell they’re doing.

- I didn’t say their systems cannot work for self-defense.

What I did was point to a couple of problems that come with the territory of re-creating an art that was lost in history. If that is something you choose to do, isn’t it better to know these things upfront?

Tony Wolf says

Hi Wim,

to date there has only been one attempt to claim a literal living lineage of Bartitsu training extending back to Barton-Wright’s day, and that seems to have been a hoax perpetrated for obscure reasons. There are judo and jujitsu schools in the UK that legitimately can trace aspects of their teaching lineage back to former Bartitsu Club instructors Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi – Tani taught at the famous London Budokwai dojo for decades – but obviously, that isn’t the same thing.

The Bartitsu revival has been underway sporadically since about 2005 but, as you note, it’s only really kicked into gear since the release of the first Guy Ritchie Sherlock Holmes movie. We used to joke about becoming popular, or even just well-known, on the assumption that it would never actually happen. That said, via discussions on the Bartitsu Forum and elsewhere, we’ve been debating all of the points you raise in this article very intensively for over ten years now (dating back well before any of us started actually teaching revived forms of Bartitsu).

The revival is deliberately very eclectic, almost “open source” in terms of its aims and methods. The Bartitsu Society does not legislate grading protocols, there is no formal rank system, etc. Some revivalists are all about re-creating Bartitsu as street-practical self defence, and they tend to use Barton-Wright’s original material more as a sort of inspiration than as a technical guideline. Others are specifically interested in the original or “canonical” material as a kind of recreational/living history martial arts training. Still others manage to blend both approaches. The gist is that having seen one approach to a Bartitsu revival doesn’t mean that you’ve seen them all.

Most of the “senior” revivalists have decades of prior experience in other Asian martial arts, combat sports, etc. and they’re well aware of the limitations *and possibilities* of reviving something like Bartitsu. We consider Barton-Wright to have begun a fascinating experiment in martial arts cross-training, which he then apparently abandoned when the original Bartitsu Club in London closed down. Many of us see our task as being to pick up where he left off, attempting to approximate where he might have taken Bartitsu if his club had prospered for another decade or so. The fact that this is a process of reinvention is taken for granted, and every practitioner/club/etc. works out their own relationship to the canonical material. Personally, I take most seriously those approaches that manage to incorporate the canonical material as well as heavy pressure testing, sparring etc.

Happy to chat about this if you’d like –

Cheers,

Tony

With regards

Wim says

Hi Tony,

Thanks for stopping by and giving some additional background information.

I agree with you; in any field there is a range of practitioners with a wide variety of interests an reasons for practicing the art. As a result, the results and success rates will probably vary just as much. This isn’t inherent to Bartitsu; I believe this is so regardless of the art that is practiced. Which was pretty much the point I wanted to make: Re-creating an (Eastern or Western, doesn’t matter) art from the past is difficult at best. The Eastern arts have been at it for a lot longer and we’ve seen some terrible travesties performed in its name. I sincerely hope that won’t be the case with Bartitsu, which is one of the reasons I wrote this. The other one is that Sherlock Holmes is just wicked cool. :-)

Thanks again for stopping by and sharing from your experience.

Wim

Kevin says

I’m late to the party, Wim, but I’d say from my experience the crossover is as bad with the people who admit they are actually trained in Eastern styles. So much of what you learn is unconscious that isolation is very difficult. I reached a silver glove in Savate and still was scolded for dragging my shing yi into it. That’s with knowledgeable teachers screaming at me. I honestly don’t think a necromancer has a chance. I think people would have more integrity if they called it something else but to claim you teach the method of X sells better.

Of course, no one in the WMA community in the US speaks to me anymore so I suspect the consensus is against me. However, like in science, truth doesn’t depend on consensus.

Great post.

Wim says

Thanks for stopping by Kevin. I tend to agree with your take on it. I could be wrong too but also speaking from experience, I think it’s a pretty tall order.

By the way.. The reason they don’t speak to you anymore might have more to do with the kind of gifts you give to people instead of your opinion on MAs. I mean, what’s the half-life of that generic lump of chocolate by now? And more importantly: is it distorting the time-space continuum already or is that for next year? :-D

Tony Wolf says

Gents, the fact that a “revived” style is a modern reinvention is taken for granted as being obvious; it’s a basic premise of the activity. The object of the reinvention is to get as close to the original model as is practical, within an acceptable degree of accuracy. “Acceptable accuracy” means different things to different people, but that premise is fundamental to martial arts revivalism.

Wim says

Tony,

I think the crux of the matter is indeed just what “acceptable accuracy” is. Now I’ll leave it to Kevin if he wants to expand on this but given his personal and professional background, as well as some of the discussions I’ve had with him in the past, I tend to agree with his point of view. Long story, so it may not be practical for the comments section here. Not my call.

Dennis Dilday says

Great post Wim. Until I saw the movie I had no idea the Sherlock had any martial arts in him (though why be surprised right?).

Fascinating story all around. Thanks,

Wim says

My pleasure Dennis, glad you enjoyed it.

Pieter says

Great post.

I think the cool thing about hybrid martial arts is the philosophy take what you need to achieve the goal. Noth using a tool and then try to figure out the goal.

I think that philosophy is the cool thing about MMA, Jeet Kunde Do, MCMAP, Bartitsu etc.Therefore i don,t think there is such a thing as a great system only people who can use a bunch of methods and principles and adapt them for their needs. Bruce Lee, Nick Diaz, George St Piere, Muhammed Ali, Captain America and Sherlock Holmes. All where different people in different situations buth they all adapt combat sports/martial arts techniques to their needs. I was kidding with the last two names:)

Kent says

One could ask the same questions about the Greek martial art Pankration, and I’ve seen a number of masters trying to revive extinct African martial arts in a similar fashion.

As you probably know, the fighting in the most recent movie version of Sherlock Holmes is very much based on wing chun, due to the involvement of Robert Downey’s wing chun teacher as fight choreographer …

Had no idea Bartitsu was being revived. Interesting article, thanks!

Wim says

To me it depends on a lot of factors but a key one is that absence of living knowledge. For instance, I don’t know anybody who’s learned the sword fighting systems the Medieval knights used from a teacher who can prove a credible lineage back to those days. I also don’t know of anybody who has actually used Western swords from that era in actual wars or duels. So I think a lot of experience and knowledge is lost forever. That doesn’t mean studying the manuscripts of those days is worthless. Only that you need to take into account the realities of reviving such a subject: you’ll never know if you’re accurate or not.

Craig Pothier says

“Another problem is the on-guard position. It is an antiquated one that, though it has benefits and made sense back then, is no longer used today. Not in competitive boxing gyms, and certainly not as a self-defense oriented boxing style. There are reasons for that but I’m not going to go into them here.”

So, can I persuade you to go into those reasons in a DIFFERENT blog post sometime in the future? I’ve often wondered about the different on guard positions I’ve been taught over the years and would be interested in hearing some musings on those differing schools of thought.

As always, a very interesting post; Thank you!

Wim says

Thanks Craig, glad to hear you enjoyed the article. I’ll add that post to my “to write” list. Though you should know, it’s pretty long. :-) So it might be a while before I get to it.