There are already many articles about how to train with edged weapons. I won’t rehash angles of attack or passing the blade; you can easily find that (and more) elsewhere. Instead, I want to focus on aspects instructors often don’t explain, assume you already know, or they simply don’t know themselves. But these aspects do matter once your life is on the line.

This won’t be a complete list though. It’s just a place to start when you look at your own edged weapon training. Perhaps you’ll fill in some holes in your practice, should they exist. If not, it might help you look at your training from a different point of view.

I also want to make the specific point that none of this is new. Humans have been fighting for millennia and these aspects are only rediscovered by those who have lost them in their training. To illustrate that, I’ll use some older sources, some of which might be unfamiliar to many readers. When you look for other sources, you’ll find contemporary ones that confirm my points. Nil novi sub sole, in many regards.

A final caveat: Everything below assumes you are legally allowed and justified to both carry and use an edged weapon in self-defense the moment you draw it.

Let’s begin.

How to train with edged weapons: “Earn the draw”

You can only truly use your knife, machete, sword, or any other edged weapon effectively if you have it in your hand. This is obvious and therefore many practitioners train to draw their weapon in a variety of circumstances, which is excellent training. What is all too often missing is what Terry Trahan once said:

“You have to earn the draw.”

Training the purely mechanical act of drawing isn’t enough; there is also managing the circumstances in which that draw happens. Violence doesn’t often happen in a sterile dojo-like environment. There is normally a specific context, an environment, a scenario if you will. This very much influences when and how you draw your blade. It also determines how likely you are to succeed before your attacker(s) can stop you. Not managing these parameters can make your weapon as useless to you as if it were still at home.

Some things to consider:

- Time all the different drawing methods you practice: left and right-hand draw, different pocket carries, inside the waistband carry, etc. Also, consider different sheaths and securing options as well as how wearing different types of clothing affects the draw. Just these alone will keep you busy for a while. Do it anyway. Next, have a friend give you the “Go” signal as he hits the stopwatch. He stops the time when you perform an agreed-upon action: a stab, slash, retreat, etc. With practice, you can develop an instinctive feel of just how fast (or slow…) you can draw your weapon in a given situation. This can then inform you about the methods of drawing mentioned in the next bullet.

- Quickdraw or hidden draw. Sometimes, no matter how fast you can draw your knife, it still won’t be fast enough due to the specifics of the situation. In those cases, a hidden draw might be a better option. Here too there are many factors involved: lighting conditions, line of sight, number of attackers/spectators, etc. Depending on these, you will usually choose between a stillness or movement-based hidden draw.

- Stillness. Position yourself so you hide the movements of your body, your arm, and hand as it slowly draws your knife. This is much more difficult than it sounds and requires dedicated practice. Train in front of a mirror, record yourself on your cellphone, and eventually with a training partner. All of these can give you feedback about where you telegraph your intent of drawing.

- Movement is when you use natural and contextually consistent movements to draw your weapon. A classic trick is to put your hand in your pocket and slowly grab the handle of the knife. But this needs to be done in a way that is not too fast, nor too slow. Otherwise, the movement draws attention and gets recognized for what it really is. Odds are the other guy then attacks you before you can finish the draw. It also needs to make sense. For instance, turning around or turning your back to your aggressor, hiding your arm movements when he can’t see them for a second. This trick works, but there has to be a believable reason for you to turn like that. It doesn’t make sense in every context and using it inappropriately again telegraphs your intent again.

- Line of sight. This is an imaginary straight line between you, your knife and your attacker. Regardless of which draw you choose, if your attacker has a clear line of sight he also (potentially) has the fastest reaction time. If at all possible, position yourself in such a way that you break the line of sight. Or place an object between you and your attacker to achieve the same goal, even if only for a second. More below.

- Misdirection and distraction. Think of a stage magician: he is right in front of you as he hides the trick in plain sight. You too can use speech, movement, or anything else to direct the attention away from the actual draw. This can be as simple as gesticulating with your hands to then placing them on your hips. Depending on your carry option, your hand is then placed on or near your weapon, allowing for a better draw if needed. Practice as explained in the previous bullet. You’ll be disappointed with your efforts early on, but keep practicing anyway.

- Distance. This is the big one: the closer you are to your aggressor(s), the less likely will you be able to draw your weapon in time to use it. There are obviously exceptions, but if your aggressor is within reach, he can smother or stop you as soon as you make a move to draw. This is why timing yourself is so important: it will give a more accurate idea of how much time you actually need to deploy your weapon. Calculate a buffer for lack of proficiency due to adrenal stress, and then you can make sound tactical decisions regarding a draw. If the conditions aren’t right, try to change them by increasing the distance between you.

- Lighting. In a well-lit environment, you might not even have a chance at a hidden draw: every move you make is potentially clearly visible to your aggressor. But in dark or low-light situations (at night, in a bar, nightclub, etc.) that may not be the case. Again, practice with a partner in varying conditions. Most of all, make good use of shadows to hide your movements, and if there is a single, bright light source (flashlight, floodlight, etc.) position yourself so it (partially) blinds your aggressor and masks your movements.

- Number of opponents. If there’s one aggressor, that’s a relatively simple (though not necessarily easy) situation. If there are multiple ones, things get complicated: each additional opponent adds another pair of eyes scrutinizing your every move. Line of sight then becomes critical, because somebody will almost always be able to spot your draw.

There are more categories to add to all of the above, but this should get you started with making your edged weapon training more realistic.

All that said: sometimes, a successful draw is not possible and you have to start the fight unarmed. This is a difficult choice to make, but sometimes it is the right one. When your life is on the line (when you pull a lethal weapon, it most likely is…) making the right choice is critical, even if it is the one you’d rather not. Meaning: you have your knife right there and it would be so much better for you if you could deploy it, but the circumstances just aren’t right. Should you go for it anyway? You’re risking your life that gamble… Case in point:

I recently covered a failed draw and its devastating consequences in detail in one of my Violence Analysis videos. In this case, it involved a firearm but the principles are the same: you need to earn the draw and the robber (fortunately) did not manage to do that. In this screenshot, you can see he violates several of the above-mentioned aspects, not least of which is line of sight.

These problems with earning the draw are not new, nor are they limited to just knives. As promised in the beginning, here are some of the older sources:

- Assassinating the king. There is an old Chinese story about Jing Ke trying to assassinate King Zheng. The movie Hero with Jet Li loosely adapted it for the big screen. In the story, the king almost dies because he cannot effectively draw his sword when Jing Ke draws a well-hidden dagger and attacks. So the first relevant lesson the story teaches is to earn the draw. The second is to adapt and overcome when faced with a problem. The king does exactly that by switching to a different method of drawing. The third is that Jing Ke may have successfully hidden and then deployed his dagger, but that in and of itself does not guarantee victory: the draw alone is not enough; you need to follow through as well.

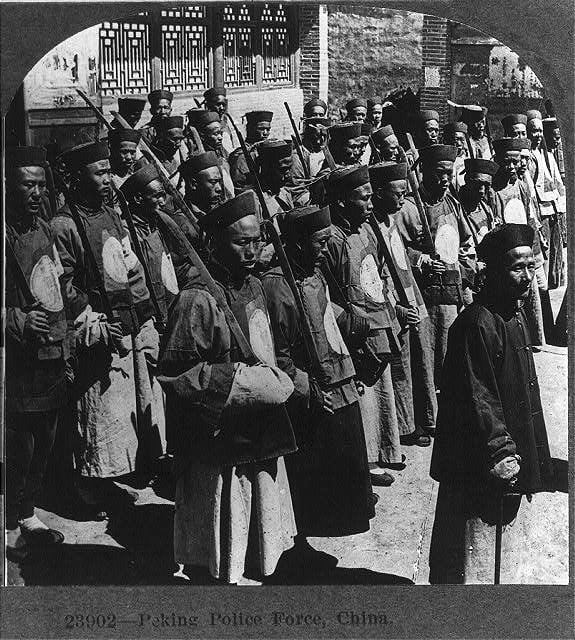

- In the Tai Chi Chuan style that I teach, we use double-edged weapons: sabre and sword. Each of these has (among other ways of training) a form. Both forms start with the weapon carried in the off-hand and you do several techniques with the weapon in that position. Only after those do you actually get to “draw” the weapon and use it as intended. The idea is that you won’t always have time to complete a draw, even though you might hold the weapon in its scabbard in your hand. Or you might have it in a traditional carry position as illustrated in the picture below and not have time to bring it into play. There are numerous reasons why a successful draw would not be possible. So the form starts out from a position of disadvantage, forcing you to work towards earning the draw.

- In one of his books, my late teacher Dan Docherty translated old texts on Tai Chi Chuan (I get a small commission for purchases made through Amazon links, at no cost to you.) One phrase in it stands out regarding edged weapons, though it applies to so much more: “Do not forsake what is near by pursuing what is far.” That can be interpreted to mean something like “closest weapon to closest target” and I’d agree with that. But it is much more; it is primarily a mindset (more on that below.) Dan would often say “do what is appropriate (for the situation)” and this applies in spades when it comes to drawing your knife: do not go for a draw you are unlikely to make when other opportunities to strike are right there in front of you.

There are other examples of course, but my point is that none of this is new. Yet people routinely overlook this aspect in their edged weapon training.

Obviously, everything you learn about earning the draw as you practice the above, also practice to spot it when somebody would use it against you…

How to train with edged weapons: Drill artifacts

Drills can be a useful addition to your edged weapons training. However, that assumes the drills are both worthwhile and performed correctly, which isn’t always the case. Some drills are just crap. Other times the drill is great but misunderstood by the students (and sometimes even the teacher), resulting in sub-optimal results. Perhaps my biggest gripe is when practitioners don’t understand that a) drills have their limits and b) you are supposed to break out of the drill.

For the first, it’s simple: no matter how good you get at drilling, it cannot come close to real life. Thinking it does or assuming skills from drills automatically translate to real life is simply wrong. I’ll give a specific example of this below…

For the second, no matter how complex the drill gets, it cannot encompass every aspect of a real encounter. So you have to actively work at incorporating the missing elements in other drills or other aspects of your training. For instance, I teach students a variety of drills. One of the modalities I often include is to break out of the drill when a mistake happens. This forces students to both not freeze and improvise when something unexpected happens (as tends to be the case in real life…)

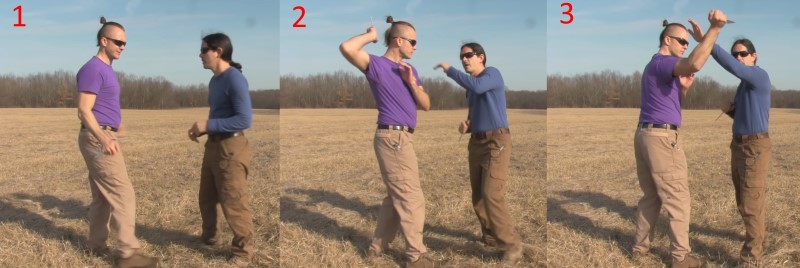

But perhaps the most problematic issue is the artifacts drills can ingrain without you actually realizing it. Case in point, watch the way the attack and block happen in this sequence:

First, I don’t know who these folks are and have no comment on their teachings, at all.

Second, I don’t know if they incorporate in their training what I’ll write next or not. So don’t see it as a criticism of them or their material. I only use this video because it is the first example of it I found. If you look, you’ll find loads and loads of people doing the same “error.” Which is:

Chambering the attack.

Take a look at the pictures below:

- Starting position.

- Chambering the attack by pulling the weapon up and back.

- Attack.

There is nothing wrong with this per se if you are just learning the drill or specific aspects need to be emphasized. In fact, I typically teach it the same way. Why? Because beginners often have a hard time getting this specific angle right and by chambering in this manner, they more quickly learn to do it properly. It also makes for a consistent and clean line of attack for the partner to practice his technique, which helps a lot at first. In essence, you create an optimal scenario for both learning to deliver that angle correctly and for your partner to most easily learn his part.

At the beginning stages of the learning process, chambering has value, but it is only a starting point: you’re supposed to eventually progress to doing your techniques without chambering. Not having this ability because you drill the chamber too much can transfer to real-life situations and end up costing you dearly.

Again, look at the pictures below:

Which one is the fastest do you think: technique 1 or 2?

They both end up hitting the same target, but 1 takes two separate movements in different directions to complete and follows the longest path.

2 takes only one fluid movement and follows the shortest path to the target. It is also not telegraphed, unlike 1.

Why does this matter?

Because in actual violent situations, time is measured in fractions of seconds. Anything you do that makes you slower and doesn’t give you a clear benefit gives your attacker a window of opportunity to use against you.

Chambering a technique because you always do so in the drill is a dangerous habit. Yet I see a surprisingly large amount of practitioners make it. Again, there is a time and place for it, but not when your life is on the line. Given the old adage of “you fight the way you train”, it would suggest avoiding ingraining this habit:

- Practice techniques going straight for a target from the position you find yourself in as you draw your knife. No wind-up, no chambering, nothing. For practice, do your draw in slow motion and freeze the moment your knife clears its sheath. That is the starting position. From there, go as directly as possible to your target while maintaining proper form and ensuring enough force in the delivery to cut or stab as needed. It takes some experimenting to each time find not just the shortest path, but also the most viable one, so don’t worry if it doesn’t feel natural at first.

- Try all techniques, all angles of attack, from that starting position. Some will work better than others. Find out what works for you before you need to apply this information.

- Use different carry positions as they will give you different starting positions. See how they influence which technique works best from there. It can be surprising to discover what makes sense when you think about it, turns out to be awkward or slow when performed at high speed.

- Do the same from positions after your partner defends against your attack or you miss. Work from those spots straight into your next attack. It’s especially in these circumstances I’ve noticed people reset or chamber their weapon like they learned in a drill. Sometimes disengaging is the best course of action, but other times pressing the attack immediately is better. Train the ability to do both.

- Do all the above while going for different targets. Some will be easily accessible from a given starting and carry position with a specific technique. But change those variables along with different targets and you’ll find things become too difficult or slow sometimes. Again, figure this out before you need it.

How to train with edged weapons: existential fear

There is a reason why I don’t like to train edged weapons with a lot of people: too many of them just “play” at training. That strikes me as suicidally stupid. Edged weapons are lethal use of force by default. Not taking it seriously is a level of negligence I find hard to understand. Obviously, that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the training. But it does mean you should avoid things like:

- Goofing off non-stop.

- Not doing the technique the instructor showed and not telling your partner about it beforehand.

- Playing gotcha with your partner by attacking in such a way he can never defend correctly. This is easy to do because you know up front what his technique will be.

- Doing surprise attacks on students while they’re busy training with another partner.

- Throwing a live blade at a student as you yell “catch!”

- Etc.

I’ve personally experienced all of these and much more. Now imagine doing the things on this list at a firing range…

How long do you think will it take before either an accident happens or you get kicked out by the range master?

Right…

Given that knives and other edged weapons qualify as lethal use of force just like firearms, why on earth wouldn’t you treat them the same way? Meaning, with the proper intent and appropriate safety practices.

What’s more, it is sloppy practice and instills the critical error I mentioned above regarding leaving out elements that are missing in training, but essential in real life. Not least of which is what I call existential fear.

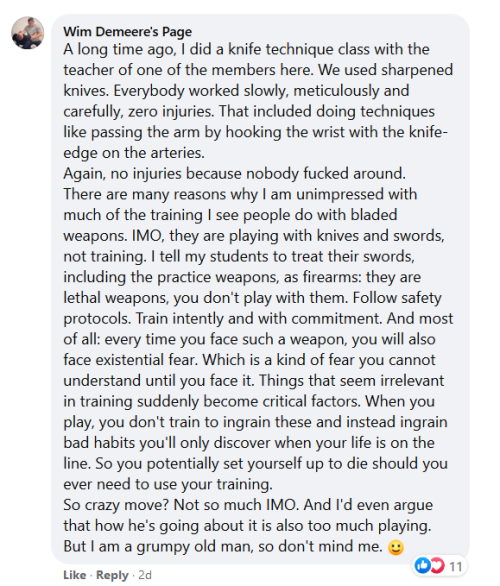

Here’s a screenshot of something I wrote a long time ago:

The self-defense and martial arts community can learn a lot from the firearms community. Especially when it comes to training protocols, safety rules but most of all, mindset.

The right mindset should be consistently present in every element of your training. Not just in what you do but also in how, why, and when. Pretending existential fear doesn’t exist or could never influence you in real life is a counterproductive mindset, to put it mildly.

Here are some elements to consider:

- Whenever you have to use a weapon (edged or otherwise) understand you may die or you may have to take a life. Those are the stakes, so take training seriously. If you can’t, then you’re either living in a fantasy world where death has no consequences or repercussions, or you simply don’t understand violence and shouldn’t be allowed to handle weapons. It’s OK if you enjoy the training and intensity that goes with it. It isn’t OK if you can’t be bothered to take it seriously. See below.

- Don’t let the realization of death always being on the table freak you out and then cheat in training:

- Don’t go fast when you’re supposed to go slow.

- Don’t move before your partner does because you know what he’s going to do and when.

- Don’t change the technique so you have an advantage you won’t have in real life

- In short, cheating in training only strokes your ego and lulls you into a false sense of security.

- It doesn’t take much skill or effort to kill somebody with a knife. The realization your life may end at the hands of a knife-wielding attacker you could easily handle if unarmed, can be hard to face. Instead of getting stuck in this fear, train so you can “flip the switch” into a different state of mind. There are several, but I prefer these two: Survivor and Hunter.

- Survivor: whatever it takes, you must survive. Preferably, by escaping and getting away from your attacker. If that is not possible, commit to going as far as you need to go to survive: there is no tapping out, no quitting. No matter what, you keep going until you are safe.

- Hunter: You are not prey, you are a hunter, regardless of who attacked who first: mentally, turn the tables on him and hunt him down in your mind. That does not necessarily mean going berserk and charging in. Instead, use whatever techniques and tactics are appropriate for the situation. But in your own mind, you are not his victim; you are the one person he should have left alone. This is easy to say, but very hard to do. Typically, it takes some previous experience with violence and also practice, which is a topic in and of itself. But it can certainly be done and can be effective in managing existential fear.

- Progression from training knives to live blades. Begin your training with soft, flexible training knives so you don’t pay too heavy a price when you mess up. As you improve your skills, use more rigid training weapons, like composite materials or wood. Eventually, you can use live blades. NOT for sparring or high-speed training, in case you need to be told this. Also not for free-flowing training where you improvise. Instead, use it for deliberate and well-defined technical training at a controlled speed. This isn’t for everybody and I don’t advise just giving it a try to see what happens. You need enough experience, technique, control, and most of all the right mindset: there is no messing around. Not by you, not by your training partner, nor anybody else. You are both responsible for making sure the knife never draws blood. Do what needs to be done so you can achieve that goal. In the end, it gives both you and your partner an intimate experience of how quickly a life can be taken with an edged weapon. It is not the same as experiencing existential fear, but it is a step in that direction. From that experience, take the same focus and intent to your non-live blade training.

- In case you find the previous bullet point over the top: first, read the screenshot above again. Second, re-read my point about this not being for beginners. Third, case in point as it relates to firearms:

A few additional things:

- I repeatedly mention experience in this article, but it is not universal. Disarming a scared teenage kid who pulls a knife on you in the street is an experience. However, it is not the same as a drug addict in a hyper-aggressive state stabbing you in the back because that’s what the voices in his head are screaming for him to do. Nor is it the same as surviving an experienced street thug trying to ram a blade between your ribs when he sets it up well. All of these are experiences and they are real to you if you live through them. But what works in one instance may be suicidal in another. I would advise you to always view your experience in the context in which it is relevant. At the same time, be cautious of extrapolating too much from it, into contexts where it might break down. There will be similarities, of course, and these are important. But so are the differences…

- If you’ve lived a sheltered life, far removed from everyday violence, your ideas and expectations regarding edged weapon use are likely to be off by a mile. This inevitably negatively influences the mindset you bring to training and in a real-life encounter. If this applies to you, it would be wise to take this into account and seek out more accurate information. There are plenty of sources out there, so just keep on looking and learning. This applies to all of us really, but perhaps more so if you are forging the right mindset from scratch.

How to train with edged weapons: Commitment

The final point is the need for commitment when you use an edged weapon in real life. Some research points to the concept of proximity being an important factor when it comes to taking lives:

It is easier to push a button that sends a missile to a target a thousand miles away than to shove cold steel into somebody until the light goes out in their eyes and you get to see and feel it happen, up close and personal.

The closer you are, the more difficult it is mentally and emotionally.

I don’t know how accurate these studies are but one thing is for sure: in the first scenario, you have no skin in the game as the violence you set into motion doesn’t affect you directly. In the second, you literally do: failure potentially means you die. So then is not the time for half-hearted attempts at anything. You need to commit to a course of action or suffer the consequences.

That doesn’t mean you have to be tactically stupid about it and not change course when needed. It means that when you go, you really go and do techniques in an effective manner. You have to be willing to:

- Feel your blade cut through muscles and tendons, potentially crippling your attacker for life.

- Hear him gasp as you ram your blade into his body and it drives the air out of his lungs.

- Feel his blood spray into your face as you cut an artery.

- Keep on fighting until blood loss, shock or organ failure stops his ability to hurt you and you feel him go limp.

- Etc.

Too graphic for you?

What did you think would happen when you use a knife on somebody?

Real life is not a movie.

It doesn’t matter if you are legally justified to use the knife in self-defense; you still need the commitment to do so effectively. That comes with a lot of baggage and things you cannot experience in training, let alone fully prepare for. Unless you are a psychopath, already have intimate experience using violence, or grew up with it. If that’s the case: this article wasn’t written for you; you already know what I am talking about.

Watch the video here for an example of what a real knife fight looks like: Knife fight in Beijing

Notice how as long as both men have a knife, they are unwilling to charge in or otherwise fully commit to an attack. Because they know there can be devastating consequences if they do and fail to end the fight right away.

It is easy to have commitment in training when you don’t face real consequences for your mistakes. Hence all the playing and “point sparring” you so often see practitioners do with training knives. When there is a guy in front of you who will gut you the first chance he gets, things are radically different. Commitment is more difficult to muster then. Which is an issue you need to address in training before you need it in real life. This brings us back to all of the above:

- Train in a realistic manner.

- Don’t cheat in training.

- Avoid errors that result from mindlessly performing drills.

- Don’t train to ignore your mistakes.

- Don’t train techniques that work, but the attacker gets to land a kill shot too. As a friend of mine says: “Dying second is not a win.”

Again, none of this is new. E.g.:

In the Tai Chi Chuan style I teach, there is a sword technique called “Li Gwong shooting an arrow at a tiger.” My teacher taught it at a seminar once and explained the story/myth behind the name. It has several versions, but you can read about it here. He pointed out that the story was about intent and commitment when defending yourself. How it is not an easy thing to do, to stab an attacker in the face and drive your sword through it. Failing to have that commitment when faced with an attacker who also has a sword likely means you die. So commitment is a primary component of successfully surviving such encounters.

Conclusion

The goal of this article is not to chastise anybody who makes the mistakes I mention above. Nor does it mean not making them automatically results in perfect performance when training to use edged weapons. We’re all merely humans and prone to errors. My goal was to share my perspective on training with edged weapons, what some of the priorities should be, and which traps to avoid. By all means, feel free to disagree or ignore it all. Or adapt it to your specific needs and carry on training. What you do should work for you. If it does, great. If not, perhaps you can find a use for the information presented here and get better results.

Nor is this a definitive list. There are plenty more issues I could have mentioned, and taken different angles of approaching the topic, but this article is already more than long enough. So take out of it what you like and hopefully you may never need to actually use your training.

Good luck.

Leave a Reply