I wrote about some of my training a while ago and in the comments section, I received this reply:

Hi Wim!

Thank you for this Post that shows that sometimes Hard work beats natural Talent.

I have almost the same problems with Flexibility and Speed as you in my Martial Arts Training (Taekwondo).

Can I ask you what was or is your specific Training to get your Fast hands? Tubes? Lots of Push ups?

Greetings from Stuttgart Germany

Tino Carta

I think this is an interesting question so instead of writing a quick comment in reply to Tino, I made this “how-to” guide here so all of you can use it. There’s a lot of ground to cover so let’s get started.

What are fast hands?

Well, obviously that means you can move your hands quickly. Which is true enough but there’s more to it in my opinion, especially in the context of martial arts.

These are the goals I had in mind when I started training to get fast hands:

- Be able to move my hands with as much speed as possible.

- Be able to go from one technique to the next as fast as possible.

- Be able to do this with accuracy.

- Be able to do this with power.

Other people will have a different definition and that’s fine; this is what works for me and I think it covers the most important aspects for martial arts. But you are obviously free to do things differently if you have different needs.

Let’s take a look at each of those points in a bit more detail before I talk about the drills and exercises.

1) Be able to move my hands with as much speed as possible.

This is self-explanatory but there are a few things I would like to emphasize.

First of all, speed can be defined in many different ways. I’m not going to go over this here but I’ll point to my own goal back then: I wanted maximum explosiveness in each movement. Explosiveness means that you go from 0 to 60Mph in as little time as possible.

After several decades of teaching and coaching people, I find this to be one of the main problems practitioners have when they want be faster: they focus on the wrong aspect of speed. In a fight, maximum speed is important as it allows you to land your techniques before your opponent has time to block them. The faster you can hit, the less time he has to stop you, the more likely you land the shot.

I think this is true.

However, if you take a relatively long time to get to that maximum speed, he has time to act.

If you work on explosiveness along with maximum speed, you’re not just trying to be fast; you’re also practicing getting to that top-speed as quickly as possible.

The difference between these two is the amount of acceleration you can bring to the technique. Even though you need both, I believe you should focus on acceleration. Simply because by doing so, more often than not, you also improve your maximum speed which makes it a two birds with one stone thing.

2) Be able to go from one technique to the next as fast as possible.

Not all forms of movement are created equal. I’ll simplify it a bit and divide it into two categories, similar to the way sports are broken up:

- Cyclic: One movement or a small set of movements are repeated over and over. An example of this is running, cycling, swimming, etc. You always do the same movement.

- Acyclic: Pretty much every action is different. Your movements constantly change not only in direction but also amplitude and the amount of activity required from each joint and the muscles attached to it. Martial arts fall directly into this movement.

Here’s the thing: speed training for cyclic movements is not the same as for acyclic movements.

Why?

Because there is no need to train the ability to change directions in cyclic movements.

Usain Bolt can focus on nothing but running in a straight line. If he’d have to dodge arrows, jump over fences and kick a football during the 100m dash, he wouldn’t be as fast as he is now. It would also be a lot more entertaining to watch him run, but I digress…

In martial arts and self-defense however, this ability is the key to success: you need to be able to punch, kick, throw, block, parry and use footwork at maximum speed but also go from one to the other without pause. If you can do this, you become faster overall not because you move faster but because you spend less time switching from one technique to the next. This is one of the differences between practitioners of a high level and those with only a limited amount of training time and experience: the former don’t waste any time while doing one technique after another whereas the latter have to spend extra time (and energy) on preparing their next move. This doesn’t seem much until you take into account that three seconds is an eternity in a fight. The fight should be over by then. So any fraction of a second you can shave off of a technique (without losing any of its effectiveness) is a good thing.

The most important factor to train this ability is deceleration, which is the opposite of acceleration, meaning: how fast you can slow down from moving at top-speed to zero. The faster you slow down to a halt, the faster you can do your next technique. And the one after that. And so on. So in contrast with other sports or activities, how fast you can go is only half the story when you fight. The other half is how fast you can stop moving and then move at maximum speed again.

3) Be able to do this with accuracy.

Blistering speed is important. But hitting the target is equally, if not even more so, important. In my experience, the faster you move your hands, the more likely you are to lose your precision to a certain degree. At least, this seems to happen in the early stages of speed development. As you get better at it, you once again become able to focus on other factors such as precision or timing while maintaining that increased speed. But this takes specific training and I’ll cover that below in the exercises.

In part, this is another aspect of decelerating. Being accurate with your techniques means you need to know where exactly you should stop your hand from moving. But it also means having crisp and clean technique. If your technique is sloppy, it will be harder to maintain accuracy as all those errors will send your hand in different directions instead of directly at the target. At high speed, you don’t have time to spare for corrections so having good technique is another key factor for fast movement in the martial arts.

4) Be able to do this with power.

One of the main drawbacks of training for fast hands is that it invariably weakens your techniques at first. As you speed up, you lose the connection to the power source (your body torquing or turning, drop-stepping, step-drag footwork, etc.) on the moment of impact and your strike becomes more of a slap than anything else. As a result, your attack loses effectiveness because that extra speed caused such a loss in power. That doesn’t seem like a good deal to me.

The way my old Sifu taught me, you can avoid this problem by cycling through a specific way of training for a given technique:

- First focus on perfect technique.

- Then increase the speed progressively as long as you can maintain proper form.

- Only then start adding power, also progressively and while maintaining speed and technique.

I still think this is the best way to improve your hand speed, or the speed of any other technique for that matter.

Another aspect, one that is all too often overlooked, is this:

What kind of power are you training for?

When I was in my early teens, I read an old book about Japanese martial arts. There were many interesting concepts in it but the one that fascinated me the most was the concept of four different kinds of impact. I spent an inordinate amount of training on this and eventually developed my own ideas on it, resulting in the five types of impact I teach:

- Penetrating

- Shockwave

- Bouncing

- Ricochet

- Ripping

This stuff isn’t unique or all that special, by the way. It’s just my take on it, what works for me. I’ve written about this in detail and have also explained it on video so I won’t go over them here. My point is this:

Movement that works for one type of impact doesn’t always work for the other. Therefor, training to be faster with a specific kind of impact will also be different for each one. There is overlap, for sure, but there are also significant differences. To the point that the one can exclude the other. For example: focusing solely on ripping impact will make it very hard to do the other ones properly. Not so vice versa.

So before you start working on making your hands go faster, the question you need to ask yourself is: what are your hands supposed to be doing?

The answer to this will change depending on the particular technique, the style or system, the context, etc. and it’s up to you to figure out what your goal really is. Once you do, you can focus on speeding up the technique for that specific impact.

Some background stuff.

Before you start on the drills, here’s some additional information so you understand where I’m coming from and why I approach this topic the way I do. Again, this is my take on things. It works for me and the people I train but it’s not the be all, end all. Feel free to tweak it to suit your needs. Here goes:

- Some people are naturally quick. Studies suggest that your genes determine how fast you can move, to a certain degree at least. Your percentage of fast twitch muscle fiber, your specific skeletal system, insertion spot of the tendons and muscles, etc. all play a role. If you’re unlucky, these factors are not in your favor and you might never be as fast as the next guy. However, you can still make a lot of progress. I’m the best example of that: I was slow when I began training. Now, I may not be the fastest guy in the world but I’m not slow anymore. So don’t give up, just keep on training.

- It’s not just about hands or arms. Just because you want to move your hands at lightning speed, doesn’t mean you should ignore your legs or the other muscles in the torso. Even if you just move your hands and arms, the rest of your body needs to stabilize itself to allow fast movement in your limbs. Furthermore, if you want to have power in those techniques, you’ll have to incorporate the rest of your body anyway. So don’t just focus on your hands and arms, work on everything.

- Find the right amount of tension. For a muscle to operate at top speed, its antagonist needs to be relaxed enough to allow this. If it isn’t, it acts like a brake and slows your movements down. So you need to be relaxed enough to move fast. But being too relaxed can make it more difficult to have explosive movements. The trick is finding the right amount of tension for you, for each specific technique. This changes from one person to the next so it’s another one of those individual study things. For the record, there is a lot more to it and I’m oversimplifying again. But the concept is easier to explain this way. Also, not all methods of generating power (and therefor speed) are created equal. So what I’m saying here doesn’t necessarily apply as much for some styles as for others. Regardless, it’s a factor that has an influence on the end result so I think you should incorporate it in your training.

- Technique is key. Get rid of parasite movements. Anything you don’t need for a given technique needs to go because it slows you down. Streamline it until you bring it back to its pure essence, only then can you get to maximum speed. You have to do this anyway if you want to increase your punching power, so it’s never wasted training.

- Technique is key, bis. Focus as much on retraction as you do on accelerating your hand towards the target. This is one of the most common mistakes I see people make when they try to speed up; too much emphasis on the strike itself and they forget about retracting the hand just as quickly. This slows down your overall speed and also causes delays when you want to combine techniques instead of doing just a single one. One way of getting around this issue is to make your techniques such that each technique ends where the next one begins. You can see this in many martial arts:

- Boxing: In the classical one-two combination, the cross starts when the jab retracts.

- Silat/Kuntao: The elbow strike is a chambered punch, the punch is a chambered elbow. Read Bob Orlando’s excellent article for more on this concept.

- Tai Chi Chuan: The expanding movements of the defensive aspect of “Grasping Bird’s Tail” is a perfect preparation for the contracting body mechanics of “Parry and Punch.”

- Etc. When you look for them, you’ll find tons and tons of examples in all styles and systems.

- It takes time. If you want to reach your ultimate speed potential, you’ll have to dedicate a lot of time to it. In particular if you are slow like I was when I started. That said, with the drills I’ll explain here below, you should see progress quickly. As in, after only a couple of weeks. But that’s just the start; reaching your maximum potential can take years. So keep going at it, there’s no other way.

- Don’t overdo it. Training for speed and explosive movement is extremely taxing on the body. Your joints, tendons and muscles really take a beating then and it’s very easy to overtrain. I would suggest you cycle different training protocols instead of doing speed-work all the time. Also, get enough rest after those sessions; it makes a difference.

Aside of all this, there is one key element I implemented when I trained for speed. It comes from a basic model of physical performance I learned a long time ago. Though it has been criticized as being incomplete (some people consider it totally wrong), I like it for its simplicity, which allows you to structure your training better.

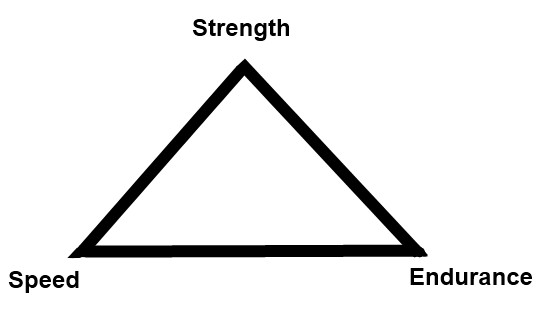

Take a look at this drawing:

In this model, the idea is that at best, you can only work on two of these physical assets at the same time. You can train for speed-endurance or speed-strength but you can’t train for speed-strength-endurance. Depending on the context, you will need the one more than the other. Here are a couple examples:

- You’re going to compete in an MMA bout. You need to be able to hit fast and hard and do so for several five-minute rounds. You’ll have to focus on all three sides of the triangle, alternating them in your training schedule.

- You train for self-defense. Your focus has to be on speed-strength. You want to hit as fast and hard as you possibly can. But you don’t need to keep this up for 15 minutes like in the cage or ring.

These are two examples on the opposite end of the scale and there’s lots of middle ground and overlap but you get what I mean: determine your goals first and then train specifically for them. If you don’t, then any success you have is in spite of your training, not thanks to it.

In my opinion, the single most important factor of this triangle is strength. If you want to be fast, build a solid foundation of strength first. The harder your muscles can contract, the faster you can potentially become. There is a point of diminishing returns of course, which is why the strongest fighters don’t necessarily hit the hardest or move the fastest. But strength helps, a lot…

Another reason to focus on strength first is that certain training methods require it. You shouldn’t start a plyometric training protocol before you have spent enough time on strength. Otherwise you dramatically increase your odds of getting injured and over-trained. I think it’s less relevant which type of strength training you do (free weights, machines, cables, suspension trainer, kettlebells, etc.), as long as you do it consistently and take into account periodization. I wrote entire chapters about this stuff in The Fighter’s Body so please check out that book for a more in-depth explanation on this.

That’s the background information I think you need to know before you start working on getting faster. I know it’s a lot but just let it digest a bit, form your own goals and then make a plan to reach them. You’ll be more successful that way than if you just wing it.

Here are some of the drills I used and still use today. They fall in two categories: conditioning and application. Conditioning concentrates on the musculoskeletal system and making it faster. Application trains you how to use the speed you gained from the conditioning. You need both, extra speed and the ingrained skill of using it in techniques.

First up, the conditioning part.

Plyometric training

This is in my opinion by far the best kind of training to increase your hand speed. This training protocol consists of exercises in which you switch from eccentric to concentric contractions in muscles as quickly as possible. The key is in making the switch as fast as you can, not in how hard the contractions actually are; that comes later. So don’t push it too hard at first, concentrate on changing directions instantly instead. Here are some drills:

1) Speed ladder.

You can buy a commercial speed ladder (especially handy if you as it’s portable), draw one on the floor with chalk or use tape. It’s all good, just use what you can get.

After a good warm up, you can start doing the exercises in this video.

In sequence, this video shows the following exercises:

- Crab walk

- Pat-a-cake crab walk

- Cross-over ant walk

- Bouncing ant walk

Do five reps in each direction and two to three sets of each exercise.

2) Push ups

Once you can comfortably do the ladder drills, work on the plyometric push ups. This video is a good example of how to get started:

You can see both the plyometric push up and the side-step push up. Do as the instructor says here and work your way up to it after doing his introductory version of the push up. I would recommend working up to ten reps for two to three sets in both exercises.

3) Pull-ups

Given the agonist/antagonist system in the human body, you need to work on the back as well. Because of the way the back muscles work, this is a whole lot more difficult and it often feels like you’re not all that explosive. Don’t worry about it, it’s normal. Just go as fast as you can and you’ll still make progress.

Check out this video:

As you can see, you definitely need a fair amount of strength for this kind of exercise. I would have dropped down a little faster for more eccentric contraction but this version works well too. Try to do five to ten reps for two to three sets.

I’m not a big fan of the kipping pull-ups you see a lot these days. The exercise has some value but in my experience, regular pull-ups done in the plyometric fashion offer a whole lot more and are also safer. But knock yourself out if you’re into this kind of thing.

4) Rows

Along with pull-ups, do the rows in this video as well:

These are easier than the pull-ups but equally important. Just make sure you keep your spine (especially the lower part) neutral and braced. Try ten to fifteen reps for two or three sets.

There are tons and tons of variations of these exercises and a bunch more that are great too. But if you start with these, you’ll get results quickly and can experiment with those alternatives afterwards.

Before you go out and do this stuff, some important information:

- Do a great warm up. Because of the explosive movements, there is an incredible amount of stress on your joints, tendons and muscles. If you don’t warm up well, you risk tearing muscles and ending up in the hospital, especially when you first start this type of training. So be smart about it and warm up.

- More isn’t better. Plyometrics is extremely effective but also very taxing on your body. Think long term instead of trying to improve your speed overnight. Even though it feels like you’re not doing enough and could do more, don’t. Overtraining and injuries will slow down your progress even more. Train this way for no more than two, maximum three times a week.

- Build a solid strength base first. Spend at least 3-6 months on regular weight training before you even attempt it. If you don’t, you’re taking stupid risks. Whats more, once you have that strength-base you’ll make progress even faster. Remember the triangle drawing here above…

- Stop when you start slowing down or use bad form. You want fast reps using perfect form. Anything else is either counterproductive or dangerous.

- Don’t combine plyometrics with other training. Meaning, you do plyometrics and nothing else along with it. Don’t do a couple of rounds on the heavy bag or a jogging session afterwards. You will have enough energy for it but the extra training will slow down your recovery time and focus too much on speed-endurance instead of speed-strength.

- Cycle properly. This is the most important piece of advice I can give you. It’s also the one most people ignore at first, until they learn the hard way why it is true. Here goes: stop after two to three weeks of plyometrics and wait at least a couple weeks before resuming this kind of training. Your body needs the recovery and you also need to train how to apply that extra speed in your techniques. Periodization in your training is crucial if you want to make consistent speed gains.

That’s it for basic conditioning. Now for the application part.

Shadowboxing

Shadowboxing is one of the best ways to make sure that the additional speed you trained so hard for will be used correctly in your techniques. Simply because there is no opponent giving you the adrenal stress that might throw your techniques off. You’re also much more in control of what to do than when you work with a partner.

I always warm up with some shadowboxing and sometimes even do entire workouts just that. It’s during those that I often work on increasing the speed of my techniques, both single ones and in combinations. It always worked well for me and my clients so I definitely recommend you give it a try. You can make this as easy or as complicated as you like, shadowboxing is extremely versatile as a training tool. It’s totally up to you how you want to drill it.

If you don’t know where to start or would like some other ideas, you might like this guide I wrote a while ago. It covers shadowboxing in detail:

The first two parts explain how to shadowbox and the last one mainly explains the reasons behind a sample workout. You can use that information as a framework for speed-training or do something entirely different. See what works best for you.

Just to give you a place to start, try this work out, using 2 min. rounds with 1 min. rest in-between:

- Warm-up: Do a solid 10-15 min. warm up to get your body ready.

- Round 1: Throw only the jab and cross. Pretend you’re sparring with a guy and you only want to use those techniques. Go at about 70-80% maximum speed. You should not be out of breath after this round, take it easy. The real work will be in the following round.

- Round 2: Throw the jab and cross like before but now go at top speed. Don’t throw combinations, just do single techniques but as fast as you can every single time and with 3-5 seconds between each punch.

- Round 3: Same as round 1 but with the left and right hook.

- Round 4: Same as round 2 but with the left and right hook.

- Round 5: Same as round 1 but with the left and right uppercut.

- Round 6: Same as round 2 but with the left and right uppercut.

- Round 7: Same as round 1 but with all the previous techniques mixed together.

- Round 8: Same as round 2 but with all the previous techniques mixed together.

- Round 9: Cool down.

This workout isn’t all that difficult however, there is one caveat: your technique has to be perfect every single time.

You do not want to ingrain sloppy, fast technique. You want to ingrain perfect, fast technique. So whenever you feel you’re starting to mess up those punches, even if only a little, either take more rest between each punch or slow down a bit until you can consistently do it the right way.

This is difficult. It takes a lot of work and concentration. But if you put in the effort, you’ll very quickly get some impressive results.

Conclusion

Having fast hands is an important part of martial arts. You don’t have to be the fastest guy in the world to be effective but being slow isn’t really helpful either. If anything, it’s not all that difficult to train for speed: it doesn’t take immensely complex drills or exercises. Nor do you need to have tons of experience for it, beginners can train speed just as much as experienced practitioners.

What you do need is some knowledge on how to train for it, a good training schedule and most of all, a lot of I-am-going-to-keep-at-it-and-will-not-give-up-until-I-get-it perseverance. In this how-to guide, I tried to give you some help for the first two. There is a lot more to this subject but at least you have someplace to start now. As for the last part, perseverance, this is something you have to provide. All I can tell you is this:

If you are slow like I was and want to have fast hands, you can have them. You just have to want it bad enough.

Good luck with your training!

Resources:

The Fighter’s Body In this book I cover periodization and how to make training schedules in a lot more detail than possible in this blog post. A lot of information about health and conditioning too.

Periodization An absolute must-have book for any serious martial artist. Once you train using this method (like all top-athletes do), you’ll be both amazed at the consistent progress and never look back.

Speed ladder A handy piece of equipment for all kinds of speed training, not just plyometrics.

How to inrcease your punching power in five minutes. My blog post on how to get rid of parasite techniques and increase your punching power. The method works for speed training too. Includes a video showing how to do it.

Tino Carta says

Thanks Wim for this awesome blog post!

It was even more detailed that I expected. Thank you for that.

I know and must do a lot of these exercises (Speed Ladder and Plyometric Pushups) but in my American Football Training (Defensive Line) and not from my Martial Arts Training.^^

I´m more than sure that your post will help me to improve my Striking.

Thank you for that and Merry Christmas!^^

Tino Carta

Wim says

My pleasure and I hope it hels you out a bit. Good luck with your training, Tino.